The Road to MX: The Evolution of AI Data Formats (INT8, Bfloat, FP8, MSFP, MX)

- Mohamed Abdelgawad

- Jan 11, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 16, 2025

If there is one factor that has driven the most significant AI efficiency gains in the past decade, it is the evolution of data formats. Industry has invested heavily in researching data formats that balance precision, range, and memory/compute efficiency. While traditional formats like integers, fixed-point, and IEEE floating-point numbers have long been the backbone of digital computing, AI has driven the need for specialized formats tailored to its nature.

This article begins with the fundamentals; integer, fixed-point, and IEEE floating-point representations, not just for completeness but to build an essential understanding of how data is encoded and scaled. From there, we’ll delve into AI-specific innovations like Google Brain Floating Point (BFloat16), FP8, Microsfot Floating Point (MSFP), and microexponents (MX) formats, exploring their precision, scaling, use cases, and memory footprint, leaving compute efficiency (silicon energy/area/speed) for a future post.

Integer

Overview and Strengths

Integer systems are simple and efficient representation of whole numbers. Like -128 to 127 for INT8 (8-bit Integer). The distribution of Integer numbering system is discrete uniform with evenly space points.

(Each "|" represents evenly spaced values. The step between two consecutive values is 1, hence no support for fractions.)

Limitations

Integers fall short at precision and range; pure integer systems can’t represent fractional values (precision). Additionally, integers have no inherent scaling factors to adjust for range. Pure integer representations are uncommon in AI. Typically, integer formats like are used in conjunction with fixed-point arithmetics.

Fixed Point

Overview and Strengths

Fixed-point introduces a fixed scaling factor alongside integer values (e.g., multiplying by 0.001 to store 0.123 as 123). Fixed-point INT8 is commonly used in AI deployment (inference) through post-training quantization, where model parameters are converted to INT8 for reduced memory and faster computation without retraining the entire model. The distribution is also discrete uniform but each step is equivalent to the scaling factor.

Limitations

Fixed point has limited dynamic range: It’s never possible to represent both small and large numbers with a fixed scaling factor without requiring a large number of bits, hence large memory footprint. For example, taking 0.001 as the fixed scaling factor, the smallest +ve non-zero value it could represent is 0.001 (1 * 0.001). However, to represent 100, you would need to store 100,000 ( because 100 = 0.001 * 100,000 ), which would require ~17 bits; more than double the number of bits the Integer system requires to represent 100.

Floating Point

Overview and Strengths

To address scaling without exploding the bit-width, floating point introduces a dynamic scaling factor, through an exponent. Taking IEEE-compliant 16-bit floating point (FP16) as an example, the format is composed, of 1-bit sign, 5-bit exponent and 10-bit fraction.

![Format of IEEE FP16 [Image by writer]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/58b0d3_d563a7afc9c44f248f415bc9384d97d0~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_436,h_144,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/58b0d3_d563a7afc9c44f248f415bc9384d97d0~mv2.png)

Sign: Determines positive (0) or negative (1).

Fraction, also known as Mantissa or significand bits : Fractional part providing precision. Numbers are normalized, meaning, there is an implicit leading 1 (binary representation). This leading 1 is not stored.

Exponent: Represents the scaling factor.

Bias: A constant (15 in FP16) to allow the exponent to represent both positive and negative values while storing it as an unsigned integer. This simplifies comparison and sorting operations.

A stored 5-bit exponent could represent 0 - 31; but 0 and 31 are reserved for special numbers (e.g Zero, NaN, Infinity, to cover in a future article). Accordingly, the effective positive range of the scaling factor is 0.00061 - 32,768.

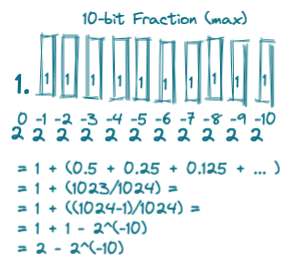

A stored 10-bit fraction in addition to the leading 1, gives a precision of 11 bits where the smallest representable normal significand value is 1 (fraction is 0). The largest representable significand value is 2−2^(−10).

Considering significand and exponent fields. The largest representable normal FP16 value would be 65504., while the minimum positive non-zero normal value is 0.000061.

The distribution of any exponent-based floating point numbering system is non-linear with denser representation near 0. This is because the scaling factor grows logarithmically (2^exponent); the step between two consecutive numbers doubles as one exponent is changed to the next, while the mantissa provides uniform precision within each exponent range.

![Visualization of the distribution of FP16 normal numbers. At each exponent, 10 significand values are swept . As the exponent is changed from one to the next, the spacing between values as significand changes gets doubled. Thus the denser representation around 0. [Plot by writer]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/58b0d3_b153f912f86a4f7fbb8edc20b0a7ab37~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_490,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/58b0d3_b153f912f86a4f7fbb8edc20b0a7ab37~mv2.png)

Limitations

While providing highly fined precision, it falls short at range; very small/large gradient updates in AI training, and large product accumulation in Matrix multiplication in AI training/Inference demand a wider dynamic range and could tolerate reduced precision. Allocating more bits to the fraction instead of the exponent can lead to underflow (very small numbers rounded to 0) or overflow (clipping to the maximum representable value) or having to scale/unscale (software overhead) the values to the representable range.

Bfloat

Overview and Strengths

In 2019, Google unveiled Brain Float (Bfloat) custom data format for AI, designed specifically for training on TPUs. The concept is straightforward: recognizing that gradients often prioritize range over precision, they increased the number of bits allocated to the exponent while reducing those for the fraction. For instance, BF16 uses 8 bits for the exponent compared to FP16's 5 bits, offering the range of FP32 while maintaining a compact 16-bit memory footprint.

![FP 16 vs Bfloat 16 data format. [Image by writer]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/58b0d3_b0571f20b5f7488fa7239c2af692dead~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_579,h_273,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/58b0d3_b0571f20b5f7488fa7239c2af692dead~mv2.png)

![Visualization of the much wider normal range of Bfloat16 compared to FP16. Normal distribution with 3-sigma and 10000 samples are used. Frequency is how many time the value was sampled. [Plot by Writer]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/58b0d3_bc82e07f26df4779a10b9e21e2d3cb99~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_640,h_480,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/58b0d3_bc82e07f26df4779a10b9e21e2d3cb99~mv2.png)

Limitations

While offering wide dynamic range, its reduced precision (equivalent to only ~3 decimal digit precision) requires caution when applied to functions/layers wherein small errors in the input values can significantly impact the output (e.g exponential, logarithmic, sigmoid functions). Additionally, in AI deployment (inference) at scale, it still incurs relatively large memory footprint compared to fixed-point INT8.

FP8

Overview and Strengths

Introduced by a joint effort from Nvidia, Intel and ARM in 2022, FP8 is a natural progression to FP16/bfloat16 towards more efficient data storage and compute acceleration, and is commonly used and natively supported in AI inference accelerators. Additionaly, using the same data, FP8 training significantly streamlines FP8 inference by eliminating the need for post-training quantization, which is typically required when deploying INT8 inference with networks trained in 32- or 16-bit floating point formats. FP8 was standardized in 2023 by Open Compute Project (OCP).

FP8 uses two formats:

E4M3 (4 exponent, 3 mantissa bits, also known as FP8P): Prioritizes precision with a smaller range. suitable for non-linear normalization and activation functions, which involve, exponentials, logarithms, sigmoids (where small errors in the input values could make big changes in the output). Recommended to be used for the weights and activations of forward passes/AI inference.

E5M2 (5 exponent, 2 mantissa bits, also known as FP8R): Prioritizes range with slightly less precision. This is better suited for backward passes where gradients can exhibit larger dynamic ranges. It is designed like a simplified version of IEEE FP16, making conversions between them easy.

![Comparison between the numerical ranges of FP8 formats e4m3 and e5m2. FP8 e4m3 (green) shows a smaller range with finer granularity, while FP8 e5m2 (red) exhibits a larger range but coarser granularity. The numbers are generated by spanning all possible exponents for each format and sampling normalized significands at regular intervals. The scatter plot provides a representative visualization of the value distribution. [Plot by writer]Limitation Overview](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/58b0d3_8a811a4c0b4b4147a5c51894c0445a28~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_420,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/58b0d3_8a811a4c0b4b4147a5c51894c0445a28~mv2.png)

Limitations

In networks where precision of FP8 is not sufficient, operations are still done in higher precision (e.g. FP16, bfloat16) and then converted back to FP8 for storage. Similarly in networks the require more dynamic range that FP8 provides, software scaling (overhead) is needed.

MSFP

Overview and Strengths

Developed by Microsoft in 2020 to achieve low-cost inference at scale (project Brainwave) eliminating the need for the manual scaling calibration required in fixed point INT8 or the relatively expensive FP16/Bfloat16 formats. The idea is smart: Instead of having a unique exponent for every element like floating point, or a single shared exponent for all elements like fixed-point, MSFP assigns one shared exponent to every n elements (bounding-box size). This shared exponent (8-bit), typically the maximum in the box, represents the range of values and helps minimize the impact of outliers to just the elements within the bounding box.

![Comparison between Microsoft Floating Point (MSFP) and IEEE Floating point (FP16) formats. MSFP assigns one shared exponent to every n elements instead of a private exponent to each element in IEEE FP. [Image by writer]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/58b0d3_469a51a67d9a42d3809ec3ee395a0e77~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_663,h_352,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/58b0d3_469a51a67d9a42d3809ec3ee395a0e77~mv2.png)

Example of converting IEEE FP16 to MSFP16

Suppose you have a bounding box of 4 FP16 values [50,25,12.5,3.125] to represent in MSFP16.

Step 1: Determine the shared exponent. (Decimal representation is used for easier understanding).

Step 2: Adjust mantissas (each mantissa is right-shifted based on the difference between the shared exponent and the individual value's exponent):

Result: The values are now stored as:

Shared exponent: 5

Mantissas: [1.5625 ,0.781, 0.39, 0.098].

This achieves ~ %50 storage reduction

Limitations

While significantly improving memory efficiency, If the n elements in a bounding box has a wide range of values (i.e. very small and very large), precision of small elements in the box will be significantly diminished since all the mantissas in that box are scaled by the largest exponent. Additionally, it is proprietary to Microsoft.

MX

Overview and Strengths

With specifications v1.0 in 2023 by OCP, MX is considered the first open standard for a family of shared-exponents datatypes. While the idea of sharing an exponent per block of elements was first implemented in MSFP, MX is the first industry’s standard with 4-bit and 6-bit FP data types for AI. The specification defines four core formats all with 8-bit shared scaling factor:

MXFP8 (E5M2, E4M3)

MXFP6 (E3M2, E2M3)

MXFP4 (E2M1)

MXINT8

The major difference between MX and MSFP is that, in addition to the shared exponent, each FP element in the block gets to keep its own private exponent addressing the precision loss of MSFP with more storage. MX is gaining support across AI accelerators/GPUs, offering an great balance between precision, range, and hardware efficiency.

Interesting fact: MX was first introduced by Microsoft and Meta at the International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA) in 2023. The exponent-sharing mechanism in the original MX differed from what was later standardized by OCP. In the initial version, a block, typically 16 elements, was further subdivided into smaller groups of 2 elements, each sharing a 1-bit exponent in addition to the block-level shared exponent.

![Comparison between MX when first introduced in ISCA 2023, and what got standardized by OCP. [Image by writer]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/58b0d3_25f26482a0bb4537b7969474b0705cc0~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_936,h_659,al_c,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/58b0d3_25f26482a0bb4537b7969474b0705cc0~mv2.png)

Conclusion and Final Note

Data formats inherently involve trade-offs between precision, range, and hardware efficiency. The landscape of data formats is vast, presenting a significant search space. Mixed-precision AI inference and training have become prevalent, leveraging different formats where they perform best.

As an ASIC designer with experience at a couple of AI hardware accelerator companies, I’ve observed a notable industry shift toward FP8 and MX formats. This trend is underscored by the considerable efforts of major companies like AMD, Arm, Intel, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Qualcomm to standardize these formats through initiatives like the OCP.

References

FP8 Formats for Deep Learning : https://arxiv.org/pdf/2209.05433

With Shared Microexponents, A Little Shifting Goes a Long Way; https://arxiv.org/pdf/2302.08007

Pushing the Limits of Narrow Precision Inferencing at Cloud Scale with Microsoft Floating Point. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/file/747e32ab0fea7fbd2ad9ec03daa3f840-Paper.pdf

OCP Microscaling Formats (MX) Specification: https://www.opencompute.org/documents/ocp-microscaling-formats-mx-v1-0-spec-final-pdf

OCP 8-bit Floating Point Specification (OFP8): https://www.opencompute.org/documents/ocp-8-bit-floating-point-specification-ofp8-revision-1-0-2023-12-01-pdf-1

Comments